غذاهای اصلاحشده ژنتیکی

غذاهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی (GM foods)، همچنین به عنوان غذاهای مهندسی ژنتیکی (غذاهای GE) یا غذاهای زیست مهندسی شناخته شده، غذاهایی هستند که از جاندارانی تولید شدهاند که با استفاده از روشهای مهندسی ژنتیک تغییراتی در DNA آنها ایجاد شدهاست. فنون مهندسی ژنتیک امکان مقایسه صفات جدید و همچنین کنترل بیشتر صفات را در مقایسه با روشهای پیشین مانند پرورش انتخابی و تولید جهش فراهم میکند.[1]

| بخشی از |

| مهندسی ژنتیک |

|---|

|

| جانداران دستکاریشده ژنتیکی |

|

| تاریخ و قانون |

|

| فرایند |

|

| کاربردها |

|

| تفاوت نگراشها |

|

|

فروش تجاری غذاهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی از سال ۱۹۹۴ آغاز شد، هنگامی که مونسانتو برای اولین بار گوجه فرنگی با ماندگاری بلند مدت خود Flavr Savr را به بازار عرضه کرد.[2][3] بیشتر اصلاحات مواد غذایی در درجه اول روی محصولات مورد تقاضای زیاد کشاورزان مانند سویا، ذرت، کلزا و پنبه متمرکز شدهاست. محصولات اصلاح شده ژنتیکی برای مقاومت در برابر پاتوژنها و علف کشها و پروفایلهای مغذی بهتر مهندسی شدهاند. دامهای اصلاح شده نیز تولید شدهاند، اگرچه، تا تاریخ نوامبر ۲۰۱۳ هیچکدام در بازار نبودند.[4]

یک اجماع علمی وجود دارد[5][6][7][8] که در حال حاضر مواد غذایی موجود در محصولات غذایی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی (GM) از نظر غذای معمولی خطر بیشتری برای سلامتی انسان ندارند،[9][10][11][12][13] اما این که هر ماده غذایی GM قبل از معرفی باید مورد آزمایش قرار گیرد.[14][15][16] با این وجود، اعضای جامعه بسیار کمتر از دانشمندان احتمال دارد غذاهای GM را بی خطر بدانند.[17][18][19][20] وضعیت قانونی و نظارتی غذاهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی در کشورها متفاوت است، در حالی که برخی از کشورها آنها را ممنوع یا محدود میکنند، و برخی دیگر مجازاتهای مختلفی را برای آنها اعمال میکنند.[21][22][23][24]

با این وجود نگرانیهای عمومی در رابطه با ایمنی مواد غذایی، تنظیم مقررات، برچسب زدن، تأثیرات زیستمحیطی، روشهای تحقیق و این واقعیت وجود دارد که برخی از بذرهای اصلاح شده به همراه کلیه گونههای جدید گیاهی، مشمول حقوق پرورش دهندگان گیاه هستند که متعلق به شرکتها میباشد.[25]

تعریف

غذاهای اصلاح شده از نظر ژنتیکی، غذاهایی هستند که از ارگانیسمهایی تولید شدهاند که با استفاده از روشهای مهندسی ژنتیک، برخلاف روشهای سنتی، تغییراتی را در DNA ایجاد کردهاند.[26][27] در ایالات متحده، وزارت کشاورزی (USDA) و سازمان غذا و دارو (FDA) استفاده از اصطلاح اصلاحات ژنتیکی را تعریف بهتری تا از مهندسی ژنتیک میدانند. در وزارت کشاورزی ایالات متحده آمریکا اصلاح ژنتیک شامل «مهندسی ژنتیک یا سایر روشهای سنتی» میشود.[28][29]

طبق گفته سازمان جهانی بهداشت، ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی (GMOs) میتوانند به عنوان ارگانیسمها (یعنی گیاهان، حیوانات یا میکروارگانیسمها) تعریف شوند که در آنها ماده ژنتیکی (DNA) به گونه ای تغییر یافتهاست که جفتگیری بهطور طبیعی اتفاق نمیافتد. این فناوری اغلب بیوتکنولوژی مدرن یا فناوری ژن نامیده میشود، گاهی اوقات به عنوان «فناوری DNA نوترکیب» یا «مهندسی ژنتیک» نیز شناخته میشود. مواد غذایی تولید شده یا ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی اغلب به عنوان غذاهای GM شناخته میشوند.[26]

تاریخ

_-_Lu%C4%8Denec_(2).jpg.webp)

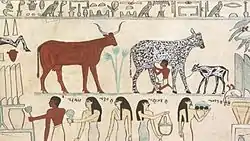

دستکاری ژنتیکی مواد غذایی به کمک انسان با اهلی کردن گیاهان و حیوانات از طریق زادگیری گزینشی در حدود ۱۰ هزار و ۵۰۰ تا ۱۰ هزار سال قبل از میلاد آغاز شد. :1 فرایند پرورش انتخابی، که در آن از ارگانیسمهایی با صفات مورد نظر (و به این ترتیب با ژنهای مورد نظر) برای تولید نسل بعدی استفاده میشود و ارگانیسمهایی که فاقد صفت هستند پرورش داده نمیشوند، آشنایی برای مفهوم جدید اصلاح ژنتیک (GM) است.[30] :1[31] :1

با کشف DNA در اوایل دهه ۱۹۰۰ و پیشرفتهای مختلف در تکنیکهای ژنتیکی در دهه ۱۹۷۰[32] امکان تغییر مستقیم دیانای و ژنها در مواد غذایی فراهم شد.

اولین گیاه اصلاح شده ژنتیکی در سال ۱۹۸۳ با استفاده از گیاه توتون مقاوم به آنتیبیوتیک تولید شد.[33] آنزیمهای میکروبی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی اولین کاربرد ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی در تولید مواد غذایی بوده و در سال ۱۹۸۸ توسط سازمان غذا و دارو ایالات متحده مورد تأیید قرار گرفت.[34] در اوایل دهه ۱۹۹۰، کیموزین نوترکیب برای استفاده در چندین کشور تاییدشد.[35] پنیر بهطور معمول با استفاده از رنت پیچیده آنزیمی که از پوشش معده گاوها استخراج شده بود ساخته میشود. دانشمندان باکتریهای را برای تولید کیموزین که قادر به لخته شدن شیر بود، اصلاح کردند و در نتیجه آن پنیر به وجود آمد.[36]

اولین ماده غذایی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی که برای پخش تصویب شد، گوجه فرنگی Flavr Savr در سال ۱۹۹۴ بود.[2] که توسط مونسانتو تولید شد، با این مهندسی ساخته شدهاست که با گذاشتن یک ژن ضد حساس، فاسد شدن آن را به تأخیر میرساند، و ماندگاری بیشتری دارد.[37] چین اولین کشوری بود که در سال ۱۹۹۳ با معرفی تنباکوهای مقاوم در برابر ویروس، محصول زراعی تراریخته را تجاری کرد.[38] در سال ۱۹۹۵، سیب زمینی Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) برای کشت به تصویب رسید، و این نخستین محصول زیست کشت در ایالات متحده بود.[39] سایر محصولات اصلاح شده ژنتیکی که در سال ۱۹۹۵ مورد تأیید بازاریابی قرار گرفتند عبارتند از: کلزا با ترکیب روغن اصلاح شده، ذرت Bt، پنبه مقاوم به علف کش برموکسینیل، پنبه Bt، سویا مقاوم شده با گلیفوزات، کدو حلوایی مقاوم در برابر ویروس، و دیگری گوجه فرنگی با ماندگاری بالا بودهاست.

دانشمندان با ساخت برنج طلایی در سال ۲۰۰۰، برای اولین بار تولید مواد غذایی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی را برای افزایش ارزش غذایی آن انجام دادند.[40]

تا سال ۲۰۱۰، ۲۹ کشور محصول بیوتکنولوژی تجاری شده را کاشتند و ۳۱ کشور دیگر تصویب نظارتی برای واردات محصولات تراریخته داده بودند.[41] ایالات متحده کشور برتر در تولید غذاهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی در سال ۲۰۱۱ بود، با بیست و پنج محصول GM تاییدیه نظارتی را دریافت کرد.[42] در سال ۲۰۱۵، ۹۲٪ ذرت، ۹۴٪ سویا و ۹۴٪ پنبه تولید شده در ایالات متحده از نژادهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی بودند.[43]

ماهی قزل آلا "AquAdvantage" اولین حیوان اصلاح شده ژنتیکی که برای استفاده در مواد غذایی در سال ۲۰۱۵ مورد تأیید قرار گرفت.[44] ماهی قزل آلا با یک ژن تنظیم کننده هورمون رشد از یک آزادماهی جویبار و پروموتر تولید شد و این امکان را برای رشد آن تنها در فصلهای بهار و تابستان در تمام سال فراهم میکرد.[45]

در آوریل ۲۰۱۶، قارچ خوراکی دکمهای اصلاح شده با استفاده از تکنیک کریسپر، تأیید de facto را در ایالات متحده دریافت کرد، پس از آنکه وزارت کشاورزی ایالات متحده آمریکا اعلام کرد دیگر نیازی به طی کردن روند نظارتی آژانس نیست. این آژانس قارچ را معاف میداند زیرا روند ویرایش مستلزم معرفی DNA خارجی نیست.[46]

بیشترین ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی که بهطور گسترده کاشته شدهاند برای تحمل علف کشها طراحی شدهاند. تا سال ۲۰۰۶ برخی از جمعیتهای علفهای هرز در برابر برخی از علف کشهای مشابه مقاومت کرده بودند. گل تاج خروس پالمر یک علف هرز است که با پنبه در رقابت است. بومی جنوب غربی ایالات متحده است و به شرق منتقل شده و اولین بار در سال ۲۰۰۶، کمتر از ۱۰ سال پس از معرفی پنبه اصلاح شده، در مقابل گلیفوزات مقاوم شد.[47][48][49]

روند

ارگانیسمهای مهندسی ژنتیکی برای کیفیتهای مطلوب در آزمایشگاه تولید و آزمایش میشوند. رایجترین روش اصلاح این است که یک یا چند ژن را به ژنوم ارگانیسم اضافه کنیم. به ندرت، ژنها برداشته میشوند یا حضور آنها افزایش یافته یا خاموش میشود یا تعداد نسخههای یک ژن افزایش یافته یا کاهش مییابد.

براساس وزارت کشاورزی ایالات متحده آمریکا، تعداد رهاسازیهای موجود در ارگانیسمهای مهندسی ژنتیک از چهار مورد در سال ۱۹۸۵ افزایش یافته و بهطور متوسط حدود ۸۰۰ مورد در سال است. تجمعی، بیش از ۱۷٬۰۰۰ نسخه تا سپتامبر ۲۰۱۳ تایید شدهاست.[50]

محصولات زراعی

میوهها و سبزیجات

پاپایا از نظر ژنتیکی برای مقاومت در برابر ویروس رینگ اسپات (PSRV) اصلاح شد. "SunUp" یک تراریخته قرمز با گوشت پاپایا Sunset است[51] نیویورک تایمز اظهار داشت، "در اوایل دهه ۱۹۹۰، صنعت پاپایا هاوایی به دلیل ویروس کشنده مرگبار پاپایا با فاجعه روبرو شد. ناجی آن یک نژاد ساخته شده بود که در برابر ویروس مقاوم بود بدون آن، صنعت پاپایا ایالت هاوایی در حال از بین رفتن بود. امروزه ۸۰٪ از پاپایای هاوایی از نظر ژنتیکی مهندسی شدهاست، و هنوز هیچ روش مرسوم یا ارگانیکی برای کنترل ویروس رینگ اسپات وجود ندارد. "[52] رقم اصلاح شده در سال ۱۹۹۸ تصویب شد.[53] در چین، یک پاپایا تراریخته مقاوم در برابر PRSV توسط دانشگاه کشاورزی جنوب چین پرورش داده شد و اولین بار در سال ۲۰۰۶ برای کاشت تجاری تأیید شد. از سال ۲۰۱۲، ۹۵٪ از پاپایا در استان گوانگدونگ و ۴۰٪ از پاپایای رشد یافته در استان هاینان از نظر ژنتیکی اصلاح شدند.[54] در هنگ کنگ، جایی که برای رشد و تولید انواع گونههای پاپایا اصلاح شده معافیت وجود دارد، بیش از ۸۰٪ از پاپایایهای رشد یافته و وارداتی تراریخته بودند.[55][56]

سیب زمینی New Leaf، یک ماده خوراکی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی است که با استفاده از باکتریهای طبیعی موجود در خاک شناخته شده با عنوان Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) برای محافظت گیاه از سوسک سیبزمینی کلرادو با عملکرد بالا ایجاد شدهاست.[33] سیب زمینی New Leaf، که در اواخر دهه ۱۹۹۰ توسط مونسانتو به بازار عرضه شد، برای بازار مواد غذایی سریع ساخته شد. پس از آنکه خرده فروشان آن را رد کردند و پردازشگران مواد غذایی به مشکلات صادرات رسیدند، تولید آن در سال ۲۰۰۱ متوقف شد.[57]

در سال ۲۰۰۵، حدود ۱۳ درصد از کدو سبز کشت شده در ایالات متحده برای مقاومت در برابر سه ویروس، اصلاح ژنتیکی شد؛ این گونه را در کانادا نیز کشت میکنند.[58][59]

در سال ۲۰۱۱، بآاساف بزرگترین شرکت صنایع شیمیایی جهان درخواست اتحادیه امنیت مواد غذایی اروپا را برای کشت و بازاریابی سیب زمینی فورتونا به عنوان خوراک و مواد غذایی تصویب کرد. سیب زمینی با افزودن ژنهای مقاوم blb1 و blb2 در برابر سوختگی سیب زمینی ساخته شده بود که از سیب زمینی وحشی مکزیکی Solanum bulbocastanum نشات میگرفت.[60][61] این سازمان در فوریه ۲۰۱۳، BASF درخواست خود را پس گرفت.[62]

در سال ۲۰۱۳، USDA واردات یک آناناس GM را که به رنگ صورتی است تأیید کرد که یک ژن حاصل از نارنگی را بیان میکند و ژنهای دیگر را سرکوب میکند و باعث افزایش تولید لیکوپن میشود. چرخه گلدهی گیاه تغییر کرده تا رشد و کیفیت یکنواخت تری حاصل شود. به گفته سازمان دولتی USDA، میوه پس از برداشت محصول، توانایی تکثیر و پایداری در محیط را ندارد. مطابق گفته دل مونت ، آناناس در یک «تک کشت» که از تولید بذر جلوگیری میکند، بهصورت تجاری رشد میکنند، زیرا گلهای گیاه در معرض منابع گردهسازگار نیستند. واردات به هاوایی به دلایل «بهداشت گیاهان» ممنوع است[63]

در سال ۲۰۱۴، USDA یک سیب زمینی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی را که توسط شرکت JR Simplot ساخته شده بود، تأیید کرد که حاوی ده اصلاح ژنتیکی است که از له شدن جلوگیری میکند و در هنگام سرخ کردن آکریلآمید کمتری تولید میکند. این تغییرات پروتئینهای خاص از سیب زمینیها را از طریق تداخل RNA به جای معرفی پروتئینهای جدید از بین میبرد.[64][65]

در فوریه سال ۲۰۱۵ سیبهای آرکتیک توسط USDA تأیید شده بودند،[66] که به اولین سیب اصلاح شده ژنتیکی برای فروش در ایالات متحده تبدیل شدند.[67] که از آرام سازی ژن برای کاهش ابراز پلی فنل اکسیداز (PPO) استفاده میشود، بنابراین از قهوه ای شدن میوه جلوگیری میشود[68]

ذرت

ذرت مورد استفاده برای مواد غذایی و و تولید اتانول برای تحمل علفکشهای مختلف و با پروتئین مخصوص از Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) که حشرات خاصی را میکشد، از نظر ژنتیکی اصلاح شدهاست.[69] حدود ۹۰ درصد از ذرت کشت شده در ایالات متحده در سال ۲۰۱۰ اصلاح شده بودهاست[70] در ایالات متحده در سال ۲۰۱۵، ۸۱٪ از سطح زمین ذرت حاوی گونه Bt و ۸۹٪ سطح زمین ذرت حاوی صفت مقاوم گلیسفات بود. ذرت را میتوان به صورت دانهای در پنکیک، کلوچه، دونات، نان و همچنین غذاهای کودک، محصولات گوشتی، غلات و برخی از فراوردههای تخمیر شده به مواد غذایی، و آرد تبدیل کرد. خمیر و آرد ماسا با پایه ذرت در تولید صدفهای تاکو، چیپس ذرت و تورتیلا استفاده میشود.[71]

محصولات مشتق شده

نشاسته ذرت و قندهای نشاسته شامل شربتها

نشاسته یا آمیلیوم یک پلی ساکارید است که توسط همه گیاهان سبز به عنوان یک ذخیره انرژی تولید میشود. نشاسته خالص یک پودر سفید، بیمزه و بیبو است. از دو نوع مولکول آمیلوز خطی و مارپیچ و آمیلوپکتین شاخه ای تشکیل شدهاست. بسته به نوع گیاه، نشاسته بهطور کلی حاوی ۲۰ تا ۲۵ درصد آمیلوز و ۷۵ تا ۸۰ درصد آمیلوپکتین از نظر وزن است.[75]

نشاسته میتواند با ایجاد نشاسته اصلاح شده برای مقاصد خاص، اصلاح شود[76] از جمله ایجاد بسیاری از قندهای موجود در غذاهای فرآوری شده. آنها شامل موارد زیر هستند:

- مالتودکسترین، یک محصول نشاسته هیدرولیز شده که به عنوان یک پرکننده و ضخیم کننده و طعم دهنده استفاده میشود.

- انواع شربتهای گلوکز، که در ایالات متحده نیز شربت ذرت نامیده میشوند، محلولهای چسبناک هستند که به عنوان شیرین کننده و ضخیم کننده در بسیاری از غذاهای فرآوری شده مورد استفاده قرار میگیرند.

- دکستروز، یک گلوکز تجاری، که توسط هیدرولیز کامل نشاسته تهیه شدهاست.

- شربت فروکتوز بالا، که با محلول دکستروز با آنزیم ایزومراز گلوکز ساخته میشود، تا زمانی که بخش قابل توجهی از گلوکز به فروکتوز تبدیل شود.

- الکلهای قندی مانند مالتیتول، اریتریتول، سوربیتول، مانیتول و هیدرولیز نشاسته هیدروژنه، شیرین کنندههایی هستند که با کاهش قندها ساخته میشوند.

لسیتین

لسیتین یک چربی طبیعی است. آن را میتوان در زرده تخم مرغ و گیاهان تولید روغن یافت. این ماده امولسیفایر است و بنابراین در بسیاری از غذاها مورد استفاده قرار میگیرد. روغن ذرت، سویا و گلرنگ منبع لسیتین هستند، اگرچه اکثر لسیتینهای تجاری موجود از سویا است.[77][78][79] لسیتین کافی فرآوری شده معمولاً با روشهای آزمایش استاندارد غیرقابل کشف است.[75] مطابق سازمان غذا و دارو آمریکا، هیچ مدرکی که لسیتین در سطوح متداول استفاده شود، خطری برای عموم نشان نمیدهد. لسیتین اضافه شده به غذاها فقط ۲ تا ۱۰ درصداست ۱ تا ۵ گرم از فسفوگلیسیریدها بهطور متوسط روزانه مصرف میشود. با این وجود، نگرانیهای مصرفکنندگان در مورد غذاهای اصلاح شده به چنین محصولاتی گسترش مییابد. این نگرانی منجر به تغییر سیاستها و مقررات در اروپا در سال ۲۰۰۰ شد، هنگامی که مقررات (EC) 50/2000 تصویب شد[81] که به برچسب زدن مواد غذایی حاوی مواد افزودنی مشتق شده از ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی، از جمله لسیتین شد.[82][83]

قند

ایالات متحده ۱۰٪ قند خود را وارد میکند، در حالی که ۹۰٪ باقی مانده از چغندر قند و نیشکر استخراج میشود. پس از مقررات زدایی در سال ۲۰۰۵، چغندرقند مقاوم به گلیفوسیات در ایالات متحده بهطور گسترده پذیرفته شد. در سال ۲۰۱۱ حدود ۹۵ هکتار چغندرقند در ایالات متحده با بذر مقاوم به گلیفوسات کاشته شد.[84] چغندرقند اصلاح شده برای کشت در ایالات متحده، کانادا و ژاپن تأیید شدهاست. چغندر اصلاح شده برای واردات و مصرف در استرالیا، کانادا، کلمبیا، اتحادیه اروپا، ژاپن، کره، مکزیک، نیوزیلند، فیلیپین، فدراسیون روسیه و سنگاپور تأیید شد.[85] پالپ حاصل از فرایند پالایش به عنوان خوراک حیوانات استفاده میشود. قند تولید شده از چغندر قند اصلاح شده حاوی هیچ پروتئین و DNA نیست - فقط ساکارز است که از نظر شیمیایی قابل تشخیص از قند تولید شده از چغندر قند غیراصلاح شده است.[75][86] تجزیه و تحلیلهای مستقل انجام شده توسط آزمایشگاههای معتبر بینالمللی نشان داد که شکر چغندرقند Roundup Ready با قند موجود از چغندرقند معمولی (غیر Roundup Ready) یکسان است.[87]

روغن گیاهی

.jpg.webp)

بیشترین روغن نباتی استفاده در ایالات متحده است از محصولات اصلاح شده کلزا،[88] ذرت،[89][90] پنبه[91] و سویا تولید میشود.[92] روغن نباتی به عنوان روغن پخت پز و تردکننده و مارگارین بهطور مستقیم به مصرفکنندگان فروخته میشود[93] و در غذاهای آماده استفاده میشود. مقدار کمی پروتئین یا DNA از محصول اصلی موجود در روغن نباتی ناچیز است.[75][94] روغن نباتی از تری گلیسیریدهای استخراج شده از گیاهان یا دانهها ساخته شده و سپس تصفیه میشود و ممکن است از طریق هیدروژناسیون بیشتر پردازش شود تا روغنهای مایع را به مواد جامد تبدیل کنند. فرایند پالایش، تمام یا تقریباً همه مواد غیر تری گلیسیرید را از بین میبرد.[95] تری گلیسیریدهای زنجیره متوسط (MCTs) جایگزینی برای چربیها و روغنهای معمولی ارائه میدهند. طول یک اسید چرب در فرایند هضم بر جذب چربی آن تأثیر میگذارد. به نظر میرسد که اسیدهای چرب در موقعیت میانی روی مولکولهای گلیسرول راحت تر جذب میشوند و بر متابولیسم بیشتر از اسیدهای چرب در موقعیتهای نهایی تأثیر میگذارند. برخلاف چربیهای معمولی، تری گلیسیریدهای زنجیره متوسط مانند کربوهیدراتها متابولیزه میشوند. آنها از پایداری اکسیداتیو استثنایی برخوردار بوده و از فاسد شدن مواد خوراکی جلوگیری میکنند.

استفادههای دیگر

خوراک دام

دام و طیور با مصرف خوراک دام پرورش مییابند که بخش اعظم آن از بقایای محصولات زراعی از جمله محصولات زراعی اصلاح شده تشکیل میشود. به عنوان مثال، تقریباً ۴۳٪ از بذر کلزا روغن است. آنچه بعد از استخراج روغن باقی میماند، وعده غذایی است که به عنوان یک ماده غذایی به خوراک دام تبدیل میشود و حاوی پروتئین کلزا است.[96] به همین ترتیب، بخش عمده ای از محصول سویا برای روغن و غذا پرورش مییابد. غذای سویا با پروتئین بالا و نان تست شده تبدیل به خوراک دام و غذای سگ میشود. ۹۸٪ محصول سویا آمریکا برای تهیه دام است.[97][98] در سال ۲۰۱۱، ۴۹٪ از برداشت ذرت ایالات متحده برای خوراک دام (از جمله درصد ضایعات دانههای تقطیر شده) استفاده شد.[99] با وجود روشهایی که هر روز حساس تر میشوند، آزمایشها هنوز بسته به نوع خوراکی که از آنها تغذیه میشود فقط با نگاه کردن به گوشت، لبنیات یا محصولات تخم مرغ یک حیوان که حاصل از سویا تغذیه میشود قادر به ایجاد تفاوت در گوشت، شیر یا تخم حیوانات نیستند. تنها راه برای تأیید حضور ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی در خوراک دام، تجزیه و تحلیل منشأ خود خوراک است. "[100]

پروتئینها

رنت ترکیبی از آنزیمها است که برای انعقاد شیر به پنیر استفاده میشود. که در معده چهارم گوسالهها موجود است، و کمیاب و گران بود، یا از منابع میکروبی که غالباً مزههای ناخوشایند ایجاد میکردند. مهندسی ژنتیک باعث شدهاست که ژنهای تولیدکننده گیاه رنت را از معده حیوانات استخراج کرده و آنها را در باکتریها، قارچها یا مخمر قرار دهند تا آنها را به تولید کیموزین، آنزیم اصلی تبدیل کند.[101][102] میکروارگانیسم اصلاح شده پس از تخمیر کشته میشود. کیموزین از مایع تخمیر جدا میشود، به طوری که کیموزین تولید شده توسط تخمیر (FPC) که توسط تولیدکنندگان پنیر مورد استفاده قرار میگیرد دارای یک توالی اسید آمینه است که با پنیر مایه گاو یکسان است.[103] بیشتر کیموزین کاربردی در آبپنیر حفظ میشود. مقدار کمی از کیموزین ممکن است در پنیر باقی بماند.

دام

دامهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی، ارگانیسمهایی از گروه گاو، گوسفند، خوک، بز، پرنده، اسب و ماهی است که برای مصرف انسان نگهداری میشوند و مواد ژنتیکی آنها (DNA) با استفاده از روشهای مهندسی ژنتیک تغییر یافتهاست. در بعضی موارد، هدف معرفی صفت جدیدی به حیوانات است که بهطور طبیعی در گونهها مشاهده نمیشود، یعنی تحویل ژن.

یک بررسی در سال ۲۰۰۳ که به نمایندگی از استانداردهای غذایی استرالیا، نیوزیلند منتشر شده آزمایش تراریخته را در مورد گونههای دامی زمینی و همچنین گونههای آبزی مانند ماهی و صدف بررسی کرد. در این بررسی تکنیکهای مولکولی مورد استفاده برای آزمایش و همچنین تکنیکهای ردیابی تراریختهها در حیوانات و محصولات و همچنین موضوعاتی در مورد ثبات تراریخته مورد بررسی قرار گرفتهاست.[104]

بعضی از پستانداران که معمولاً برای تولید مواد غذایی مورد استفاده قرار میگیرند، برای تولید محصولات غیر غذایی اصلاح شدهاند، عملی که گاهی به آن فارمینگ گفته میشود.

سلامت و امنیت

یک اجماع علمی وجود دارد[5][6][7][8] که در حال حاضر مواد غذایی موجود در محصولات غذایی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی از نظر غذای معمولی خطر بیشتری برای سلامتی انسان ندارند،[9][10][11][12][13] اما این که هر ماده غذایی اصلاح شده ژنتیکی قبل از معرفی باید مورد آزمایش قرار گیرد.[14][15][16] با این وجود، اعضای جامعه بسیار کمتر از دانشمندان احتمال دارد غذاهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی را بی خطر بدانند.[17][18][19][20] وضعیت قانونی و نظارتی غذاهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی در کشورها متفاوت است، در حالی که برخی از کشورها آنها را ممنوع یا محدود میکنند، و برخی دیگر مجازاتهای مختلفی را با آنها اعمال میکنند و در برخی نیز مصرف آنها آزاد است.[21][22][23][24]

آزمایش کردن

وضعیت قانونی و نظارتی غذاهای اصلاح شده بر حسب کشور متفاوت است، در حالی که برخی از کشورها آنها را ممنوع یا محدود میکنند، و برخی دیگر مجازاتهای مختلفی را با آنها در اختیار دارند.[21][22][23][24] کشورهایی مانند ایالات متحده، کانادا، لبنان و مصر از معادله قابل توجهی استفاده میکنند تا تشخیص دهند که آیا آزمایش بیشتری لازم است، در حالی که بسیاری از کشورها مانند کشورهای اتحادیه اروپا، برزیل و چین فقط مجوز کشت ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی را به صورت موردی مجاز میکنند. در ایالات متحده، FDA مشخص کرد که ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی به عنوان افزودنی مجاز بهطور کلی ایمن شناخته شده و بنابراین اگر محصول ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی از نظر کاملاً معادل محصول غیر اصلاح شده باشد، آزمایش اضافی احتیاج ندارد.[110] در صورت یافتن مواد جدید، آزمایشهای بیشتر ممکن است لازم باشد تا نگرانیها در مورد سمی بودن نهان، حساسیت زایی، انتقال ژن احتمالی به انسان یا برخورد ژنتیکی به موجودات دیگر را برآورده سازد.[26]

مقررات

مقررات دولتها در مورد توسعه و آزادسازی GMO بین کشورها بسیار متفاوت است. اختلافات مشخص شده مقررات GMO را در مقررات آمریکا و مقررات GMO در اتحادیه اروپا از هم جدا میکند.[24] مقررات بسته به میزان مصرف محصول مورد نظر نیز متفاوت است. به عنوان مثال، یک محصول که برای استفاده از مواد غذایی در نظر گرفته نشدهاست، بهطور کلی توسط مقامات مسئول ایمنی مواد غذایی مورد بررسی قرار نمیگیرد.[111]

برچسب زدن

از سال ۲۰۱۵، در ۶۴ کشور جهان محصولات GMO اجبار به برچسب زدن در بازار دارند.[112]

سیاست ملی ایالات متحده و کانادا این است که فقط با توجه به تفاوتهای مهم در ترکیب یا اثرات بهداشتی مستند، به برچسب نیاز داشته باشد، اگرچه برخی از ایالتهای ایالات متحده مانند (ورمونت، کانکتیکات و ماین قوانینی را تصویب کردند که به برچسب زدن محصولات اصلاح شده در این ایالات اجباری است.[113][114][115][116] در ژوئیه سال ۲۰۱۶، قانون عمومی ۱۱۴–۲۱۴ برای تنظیم برچسب زدن مواد غذایی GMO به تصویب رسید.

تشخیص

آزمایش روی ارگانیسمهای اصلاح شده ژنتیکی در مواد غذایی و خوراکی بهطور معمول با استفاده از تکنیکهای مولکولی مانند واکنش زنجیرهای پلیمراز و بیوانفورماتیک انجام میشود.[117]

جستارهای وابسته

- محصولات اصلاح شده ژنتیکی

- جانداران دستکاریشده ژنتیکی

- شیمی درمانی

منابع

- GM Science Review First Report بایگانیشده در اکتبر ۱۶, ۲۰۱۳ توسط Wayback Machine, Prepared by the UK GM Science Review panel (July 2003). Chairman Professor Sir David King, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK Government, P 9

- James, Clive (1996). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995" (PDF). The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Weasel, Lisa H. 2009. Food Fray. Amacom Publishing

- "Consumer Q&A". FDA. 2009-03-06. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- Nicolia, Alessandro; Manzo, Alberto; Veronesi, Fabio; Rosellini, Daniele (2013). "An overview of the last 10 years of genetically engineered crop safety research" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 34 (1): 77–88. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.823595. PMID 24041244. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

We have reviewed the scientific literature on GE crop safety for the last 10 years that catches the scientific consensus matured since GE plants became widely cultivated worldwide, and we can conclude that the scientific research conducted so far has not detected any significant hazard directly connected with the use of GM crops.

The literature about Biodiversity and the GE food/feed consumption has sometimes resulted in animated debate regarding the suitability of the experimental designs, the choice of the statistical methods or the public accessibility of data. Such debate, even if positive and part of the natural process of review by the scientific community, has frequently been distorted by the media and often used politically and inappropriately in anti-GE crops campaigns.

- "State of Food and Agriculture 2003–2004. Agricultural Biotechnology: Meeting the Needs of the Poor. Health and environmental impacts of transgenic crops". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

Currently available transgenic crops and foods derived from them have been judged safe to eat and the methods used to test their safety have been deemed appropriate. These conclusions represent the consensus of the scientific evidence surveyed by the ICSU (2003) and they are consistent with the views of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002). These foods have been assessed for increased risks to human health by several national regulatory authorities (inter alia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, the United Kingdom and the United States) using their national food safety procedures (ICSU). To date no verifiable untoward toxic or nutritionally deleterious effects resulting from the consumption of foods derived from genetically modified crops have been discovered anywhere in the world (GM Science Review Panel). Many millions of people have consumed foods derived from GM plants - mainly maize, soybean and oilseed rape - without any observed adverse effects (ICSU).

- Ronald, Pamela (May 5, 2011). "Plant Genetics, Sustainable Agriculture and Global Food Security". Genetics. 188 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128553. PMC 3120150. PMID 21546547. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

There is broad scientific consensus that genetically engineered crops currently on the market are safe to eat. After 14 years of cultivation and a cumulative total of 2 billion acres planted, no adverse health or environmental effects have resulted from commercialization of genetically engineered crops (Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Committee on Environmental Impacts Associated with Commercialization of Transgenic Plants, National Research Council and Division on Earth and Life Studies 2002). Both the U.S. National Research Council and the Joint Research Centre (the European Union's scientific and technical research laboratory and an integral part of the European Commission) have concluded that there is a comprehensive body of knowledge that adequately addresses the food safety issue of genetically engineered crops (Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health and National Research Council 2004; European Commission Joint Research Centre 2008). These and other recent reports conclude that the processes of genetic engineering and conventional breeding are no different in terms of unintended consequences to human health and the environment (European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation 2010).

- But see also:

- "Statement by the AAAS Board of Directors On Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods" (PDF). American Association for the Advancement of Science. October 20, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

The EU, for example, has invested more than €300 million in research on the biosafety of GMOs. Its recent report states: "The main conclusion to be drawn from the efforts of more than 130 research projects, covering a period of more than 25 years of research and involving more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than e.g. conventional plant breeding technologies." The World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the British Royal Society, and every other respected organization that has examined the evidence has come to the same conclusion: consuming foods containing ingredients derived from GM crops is no riskier than consuming the same foods containing ingredients from crop plants modified by conventional plant improvement techniques.

- A decade of EU-funded GMO research (2001–2010) (PDF). Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Biotechnologies, Agriculture, Food. European Commission, European Union. 2010. doi:10.2777/97784. ISBN 978-92-79-16344-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- "AMA Report on Genetically Modified Crops and Foods (online summary)". American Medical Association. January 2001. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

A report issued by the scientific council of the American Medical Association (AMA) says that no long-term health effects have been detected from the use of transgenic crops and genetically modified foods, and that these foods are substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts. (from online summary prepared by ISAAA)" "Crops and foods produced using recombinant DNA techniques have been available for fewer than 10 years and no long-term effects have been detected to date. These foods are substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts. (from original report by انجمن پزشکی آمریکا: )

- "Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms: United States. Public and Scholarly Opinion". Library of Congress. June 9, 2015. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

Several scientific organizations in the US have issued studies or statements regarding the safety of GMOs indicating that there is no evidence that GMOs present unique safety risks compared to conventionally bred products. These include the National Research Council, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Medical Association. Groups in the US opposed to GMOs include some environmental organizations, organic farming organizations, and consumer organizations. A substantial number of legal academics have criticized the US's approach to regulating GMOs.

- National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering; Division on Earth Life Studies; Board on Agriculture Natural Resources; Committee on Genetically Engineered Crops: Past Experience Future Prospects (2016). Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (US). p. 149. doi:10.17226/23395. ISBN 978-0-309-43738-7. PMID 28230933. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

Overall finding on purported adverse effects on human health of foods derived from GE crops: On the basis of detailed examination of comparisons of currently commercialized GE with non-GE foods in compositional analysis, acute and chronic animal toxicity tests, long-term data on health of livestock fed GE foods, and human epidemiological data, the committee found no differences that implicate a higher risk to human health from GE foods than from their non-GE counterparts.

- "Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

Different GM organisms include different genes inserted in different ways. This means that individual GM foods and their safety should be assessed on a case-by-case basis and that it is not possible to make general statements on the safety of all GM foods.

GM foods currently available on the international market have passed safety assessments and are not likely to present risks for human health. In addition, no effects on human health have been shown as a result of the consumption of such foods by the general population in the countries where they have been approved. Continuous application of safety assessments based on the Codex Alimentarius principles and, where appropriate, adequate post market monitoring, should form the basis for ensuring the safety of GM foods.

- Haslberger, Alexander G. (2003). "Codex guidelines for GM foods include the analysis of unintended effects". Nature Biotechnology. 21 (7): 739–41. doi:10.1038/nbt0703-739. PMID 12833088.

These principles dictate a case-by-case premarket assessment that includes an evaluation of both direct and unintended effects.

- Some medical organizations, including the British Medical Association, advocate further caution based upon the اصل احتیاطی:

- Funk, Cary; Rainie, Lee (January 29, 2015). "Public and Scientists' Views on Science and Society". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

The largest differences between the public and the AAAS scientists are found in beliefs about the safety of eating genetically modified (GM) foods. Nearly nine-in-ten (88%) scientists say it is generally safe to eat GM foods compared with 37% of the general public, a difference of 51 percentage points.

- Marris, Claire (2001). "Public views on GMOs: deconstructing the myths". EMBO Reports. 2 (7): 545–48. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve142. PMC 1083956. PMID 11463731. Archived from the original on 7 اكتبر 2016. Retrieved 13 سپتامبر 2019. Check date values in:

|archive-date=(help) - Final Report of the PABE research project (December 2001). "Public Perceptions of Agricultural Biotechnologies in Europe". Commission of European Communities. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Scott, Sydney E.; Inbar, Yoel; Rozin, Paul (2016). "Evidence for Absolute Moral Opposition to Genetically Modified Food in the United States" (PDF). Perspectives on Psychological Science. 11 (3): 315–24. doi:10.1177/1745691615621275. PMID 27217243. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms". Library of Congress. June 9, 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Bashshur, Ramona (February 2013). "FDA and Regulation of GMOs". American Bar Association. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Sifferlin, Alexandra (October 3, 2015). "Over Half of E.U. Countries Are Opting Out of GMOs". Time. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Lynch, Diahanna; Vogel, David (April 5, 2001). "The Regulation of GMOs in Europe and the United States: A Case-Study of Contemporary European Regulatory Politics". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Cowan, Tadlock (18 Jun 2011). "Agricultural Biotechnology: Background and Recent Issues" (PDF). Congressional Research Service (Library of Congress). pp. 33–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- World Health Organization. "Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- "Genetically engineered foods". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Glossary of Agricultural Biotechnology Terms". United States Department of Agriculture. 27 February 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Questions & Answers on Food from Genetically Engineered Plants". US Food and Drug Administration. 22 Jun 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Daniel Zohary; Maria Hopf; Ehud Weiss (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Plants in the Old World. Oxford University Press.

- Clive Root (2007). Domestication. Greenwood Publishing Groups.

- Jackson, DA; Symons, RH; Berg, P (1 October 1972). "Biochemical Method for Inserting New Genetic Information into DNA of Simian Virus 40: Circular SV40 DNA Molecules Containing Lambda Phage Genes and the Galactose Operon of Escherichia coli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 69 (10): 2904–09. Bibcode:1972PNAS...69.2904J. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.10.2904. PMC 389671. PMID 4342968.

- Bawa, A. S.; Anilakumar, K. R. (2016-12-04). "Genetically modified foods: safety, risks and public concerns – a review". Journal of Food Science and Technology. 50 (6): 1035–46. doi:10.1007/s13197-012-0899-1. ISSN 0022-1155. PMC 3791249. PMID 24426015.

- "FDA Approves 1st Genetically Engineered Product for Food". Los Angeles Times. 24 March 1990. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Staff, National Centre for Biotechnology Education (2006). "Chymosin". Archived from the original on May 22, 2016.

- Campbell-Platt, Geoffrey (26 August 2011). Food Science and Technology. Ames, Iowa: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5782-0.

- Bruening, G.; Lyons, J. M. (2000). "The case of the FLAVR SAVR tomato". California Agriculture. 54 (4): 6–7. doi:10.3733/ca.v054n04p6. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- James, Clive (2010). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995: The First Decade of Crop Biotechnology". ISAAA Briefs No. 1: 31.

- Genetically Altered Potato Ok'd For Crops Lawrence Journal-World - 6 May 1995

- Ye, Xudong; Al-Babili, Salim; Klöti, Andreas; Zhang, Jing; Lucca, Paola; Beyer, Peter; Potrykus, Ingo (2000-01-14). "Engineering the Provitamin A (β-Carotene) Biosynthetic Pathway into (Carotenoid-Free) Rice Endosperm". Science. 287 (5451): 303–05. Bibcode:2000Sci...287..303Y. doi:10.1126/science.287.5451.303. PMID 10634784.

- Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2011 بایگانیشده در ۱۰ فوریه ۲۰۱۲ توسط Wayback Machine ISAAA Brief ISAAA Brief 43-2011. Retrieved 14 October 2012

- James, C (2011). "ISAAA Brief 43, Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2011". ISAAA Briefs. Ithaca, New York: International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA). Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- "Adoption of Genetically Engineered Crops in the U.S." Economic Research Service, USDA. Archived from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Aquabounty Cleared to Sell Salmon in the USA for Commercial Purposes". FDA. 2019-06-19. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Bodnar, Anastasia (October 2010). "Risk Assessment and Mitigation of AquAdvantage Salmon" (PDF). ISB News Report. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Waltz, Emily (2016). "Gene-edited CRISPR mushroom escapes US regulation". Nature. 532 (7599): 293. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..293W. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19754. PMID 27111611.

- Culpepper, Stanley A; et al. (2006). "Glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) confirmed in Georgia". Weed Science. 54 (4): 620–26. doi:10.1614/ws-06-001r.1.

- Gallant, Andre. "Pigweed in the Cotton: A superweed invades Georgia". Modern Farmer.

- Webster, TM; Grey, TL (2015). "Glyphosate-Resistant Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) Morphology, Growth, and Seed Production in Georgia". Weed Science. 63 (1): 264–72. doi:10.1614/ws-d-14-00051.1.

- Fernandez-Cornejo J, Wechsler S, Livingston M, Mitchell L (February 2014). "Genetically engineered crops in the United States". Economic Research Service.

- Gonsalves, D. (2004). "Transgenic papaya in Hawaii and beyond". AgBioForum. 7 (1&2). Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Ronald, Pamela; McWilliams, James (May 14, 2010). "Genetically Engineered Distortions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- "The Rainbow Papaya Story". Hawaii Papaya Industry Association. Archived from the original on 2015-01-07. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Li, Y; et al. (April 2014). "Biosafety management and commercial use of genetically modified crops in China". Plant Cell Reports. 33 (4): 565–73. doi:10.1007/s00299-014-1567-x. PMID 24493253.

- Loo, Jacky Fong-Chuen; But, Grace Wing-Chiu; Kwok, Ho-Chin; Lau, Pui-Man; Kong, Siu-Kai; Ho, Ho-Pui; Shaw, Pang-Chui (2019). "A rapid sample-to-answer analytical detection of genetically modified papaya using loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay on lab-on-a-disc for field use". Food Chemistry. 274: 822–830. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.049. ISSN 0308-8146. PMID 30373016.

- "Genetically Modified Organisms (Control of Release) Ordinance Cap. 607: Review of the Exemption of Genetically Modified Papayas in Hong Kong" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "The History and Future of GM Potatoes". Potatopro.com. 2010-03-10. Archived from the original on 12 اكتبر 2013. Retrieved 2012-12-29. Check date values in:

|archivedate=(help) - Johnson, Stanley R. (February 2008). "Quantification of the Impacts on US Agriculture of Biotechnology-Derived Crops Planted in 2006" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Center for Food and Agricultural Policy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- "GMO Database: Zucchini (courgette)". GMO Compass. November 7, 2007. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- "Business BASF applies for approval for another biotech potato". Research in Germany. November 17, 2011. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Burger, Ludwig (October 31, 2011). "BASF applies for EU approval for Fortuna GM potato". Reuters. Frankfurt. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- Turley, Andrew (February 7, 2013). "BASF drops GM potato projects". Royal Society of Chemistry News. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Perkowski, Mateisz (April 16, 2013). "Del Monte Gets Approval to Import GMO Pineapple". Food Democracy Now.

- Pollack, Andrew (November 7, 2014). "U.S.D.A. Approves Modified Potato. Next Up: French Fry Fans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 اكتبر 2019. Retrieved 13 سپتامبر 2019. Check date values in:

|archivedate=(help) - "Availability of Petition for Determination of Nonregulated Status of Potato Genetically Engineered for Low Acrylamide Potential and Reduced Black Spot Bruise". Federal Register. May 3, 2013. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Pollack, A. (February 13, 2015). "Gene-Altered Apples Get U.S. Approval". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Tennille, Tracy (February 13, 2015). "First Genetically Modified Apple Approved for Sale in U.S." Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- "How'd we 'make' a nonbrowning apple?". Okanagan Specialty Fruits. 2011-12-07. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- "Know Before You Grow". National Corn Growers Association. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011.

- "Acreage NASS" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Board annual report. June 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- "Corn-Based Food Production in South Dakota: A Preliminary Feasibility Study" (PDF). South Dakota State University, College of Agriculture and Biological Sciences, Agricultural Experiment Station. June 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Padgette SR, et al (1995) Development, identification, and characterization of a glyphosate-tolerant soybean line بایگانیشده در ۲۳ ژوئن ۲۰۱۵ توسط Wayback Machine. Crop Sci 35:1451-1461.

- Staff, USDA Economic Research Service. Last updated: January 24, 2013 Wheat Background بایگانیشده در ۲۳ اوت ۲۰۱۸ توسط Wayback Machine

- "Petitions for Determination of Nonregulated Status". USDA. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Jaffe, Greg (Director of Biotechnology at the Center for Science in the Public Interest) (February 7, 2013). "What You Need to Know About Genetically Engineered Food". Atlantic. Archived from the original on 27 اكتبر 2019. Retrieved 13 سپتامبر 2019. Check date values in:

|archivedate=(help) - "International Starch: Production of corn starch". Starch.dk. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- "Lecithin". October 2015. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Opinion: Lecithin". August 10, 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Corn Oil, 5th Edition" (PDF). Corn Refiners Association. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "Regulation (EC) 50/2000". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 16 اكتبر 2013. Retrieved 13 سپتامبر 2019. Check date values in:

|archivedate=(help) - Marx, Gertruida M. (December 2010). "Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Health Sciences" (PDF). Monitoring of Genetically Modified Food Products in South Africa]. South Africa: University of the Free State. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-09.

- Davison, John; Bertheau, Yves Bertheau (2007). "EU regulations on the traceability and detection of GMOs: difficulties in interpretation, implementation and compliance". CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources. 2. doi:10.1079/pavsnnr20072077.

- "ISAAA Brief 43-2011. Executive Summary: Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2011". Isaaa.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2009). Sugar Beet: White Sugar (PDF). p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Klein, Joachim; Altenbuchner, Josef; Mattes, Ralf (1998-02-26). "Nucleic acid and protein elimination during the sugar manufacturing process of conventional and transgenic sugar beets". Journal of Biotechnology. 60 (3): 145–53. doi:10.1016/S0168-1656(98)00006-6. PMID 9608751.

- "Soyatech.com". Soyatech.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- "Poster of corn products" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- "Food Fats and Oils" (PDF). Institute of Shortening and Edible Oils. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2007. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- "Twenty Facts about Cottonseed Oil". National Cottonseed Producers Association. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015.

- Simon, Michelle (August 24, 2011). "ConAgra Sued Over GMO '100% Natural' Cooking Oils". Food Safety News. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "ingredients of margarine". Imace.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- "USDA Protein(g) in Fats and Oils". Archived from the original on 5 اكتبر 2018. Retrieved 2015-05-31. Check date values in:

|archivedate=(help) - Crevel, R.W.R.; Kerkhoff, M.A.T.; Koning, M.M.G (2000). "Allergenicity of refined vegetable oils". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 38 (4): 385–93. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00158-1. PMID 10722892.

- "What is Canola Oil?". CanolaInfo. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- David Bennett for Southeast Farm Press, February 5, 2003 World soybean consumption quickens بایگانیشده در ۲۰۰۶-۰۶-۰۵ توسط Wayback Machine

- "Soybean". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- "2012 World of Corn, National Corn Growers Association" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- Staff, GMO Compass. December 7, 2006. Genetic Engineering: Feeding the EU's Livestock بایگانیشده در ۱۲ ژانویه ۲۰۱۷ توسط Wayback Machine

- Emtage, JS; Angal, S; Doel, MT; Harris, TJ; Jenkins, B; Lilley, G; Lowe, PA (1983). "Synthesis of calf prochymosin (prorennin) in Escherichia coli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (12): 3671–75. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80.3671E. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.12.3671. PMC 394112. PMID 6304731.

- Harris TJ, Lowe PA, Lyons A, Thomas PG, Eaton MA, Millican TA, Patel TP, Bose CC, Carey NH, Doel MT (April 1982). "Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of cDNA coding for calf preprochymosin". Nucleic Acids Research. 10 (7): 2177–87. doi:10.1093/nar/10.7.2177. PMC 320601. PMID 6283469.

- "Chymosin". GMO Compass. Archived from the original on 2015-03-26. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- Harper, G.S. , Brownlee, A. , Hall, T.E. , Seymour, R. , Lyons, R. and Ledwith, P. (2003). "Global progress toward transgenic food animals: A survey of publicly available information" (PDF). Food Standards Australia and New Zealand. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Rick MacInnes-Rae, Rick (November 27, 2013). "GMO salmon firm clears one hurdle but still waits for key OKs AquaBounty began seeking American approval in 1995". CBC News. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Pollack, Andrew (May 21, 2012). "An Entrepreneur Bankrolls a Genetically Engineered Salmon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 اكتبر 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2012. Check date values in:

|archivedate=(help) - Staff (December 26, 2012). "Draft Environmental Assessment and Preliminary Finding of No Significant Impact Concerning a Genetically Engineered Atlantic Salmon" (PDF). Federal Register. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- Naik, Gautam (September 21, 2010). "Gene-Altered Fish Closer to Approval". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "FDA takes several actions involving genetically engineered plants and animals for food" (Press release). Office of the Commissioner of the FDA. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- Emily Marden, Risk and Regulation: U.S. Regulatory Policy on Genetically Modified Food and Agriculture بایگانیشده در ۸ نوامبر ۲۰۱۹ توسط Wayback Machine 44 B.C.L. Rev. 733 (2003).

- "The History and Future of GM Potatoes". PotatoPro.com. 2013-12-11. Archived from the original on 12 اكتبر 2013. Retrieved 13 سپتامبر 2019. Check date values in:

|archivedate=(help) - "International Labeling Laws". Center for Food Safety. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Chokshi, Niraj (9 May 2014). "Vermont just passed the nation's first GMO food labeling law. Now it prepares to get sued". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "The Regulation of Genetically Modified Food". Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Van Eenennaam, Alison; Chassy, Bruce; Kalaitzandonakes, Nicholas; Redick, Thomas (2014). "The Potential Impacts of Mandatory Labeling for Genetically Engineered Food in the United States" (PDF). Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 54 (April 2014). ISSN 1070-0021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

To date, no material differences in composition or safety of commercialized GE crops have been identified that would justify a label based on the GE nature of the product.

- Hallenbeck, Terri (2014-04-27). "How GMO labeling came to pass in Vermont". Burlington Free Press. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- "EU GMO testing homepage". European Commission Join Research Centre. 2012-11-20. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2015.